How to use this Guide

This guide supports you through the process of answering your question. It might help if you first write down all of your questions. After, have a look at the overview. Which parts of the guide might be useful for you? Go through all of these pages and see if you can find an answer.

Please make sure to follow this step-by-step guide before you schedule a consult! Additionally, you can have a look at our FAQ page. Maybe somebody asked the same question as you. If both the guide and the FAQ can't answer your question, you can schedule a consult with us. The link for the schedule planner can be found under Step 4: Schedule a Consult.

P.S. Here is a link to the book that is used in your data analysis courses. Take a look there, too!

1. Getting started

Guide on how to write your research

This is the ‘Research Methods Tool Box’, which helps students to conduct research.

NEW: More micro-lectures that can assist you throughout the research process can be found here.

It also may help supervisors to instruct their students.

Following questions are given attention to:

How to find and select literature?

A literature review will help you to formulate the problem you are tackling, to know what research has already been carried out on your subject and what aspects are under-researched, and will also tell you about the relevant theories, important variables etc.

A good starting place to find further relevant literature is to simply look at the articles and books your text books refer to. A more systematic review can be done using the academic databases and search engines like Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar. Often, you will find a large amount of literature relevant to your topic; articles and books that have been frequently cited by others can be prioritised. References in articles can be used to find older literature and the option ‘cited by’ can be used to find newer literature. Use the SFX link to see whether the article or book is available at our university.

Make sure to keep a good record of where you get your information from. You are advised to download and install a programme like EndNote which will help you to manage your references and bibliography. All aforementioned databases and search engines allow direct and automatic importation of citations into EndNote (and similar programmes).

When creating a list of references at the end of the paper, use one single style. At his university we suggest using the APA style. Help on citations can be found here. A list of do’s and don’ts when referring to literature can be found here.

Basic readings

BBabbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 17.

How to construct a research proposal?

A research proposal sets out what you intend to achieve and how you will go about it. Lots of information about writing a research proposal can be found here. The requirements of research proposals differ depending on the question you want to address. Research projects aiming at finding generalized knowledge (empirical research projects) should at least include (although not necessarily in this order):

Introduction

An important starting point is to explain the real-world significance of the topic and the project. You must show that there is a particular question or problem related to this topic that deserves to be studied. Do not start a research proposal with a lengthy discussion of the context. Mention the problem or question you want to tackle in the first section. Explain context and reasons for studying the topic later. This helps the reader and the writer to focus. It is very unlikely that you are the first to study this topic, so refer to the most relevant literature in the introduction. This summarizes what has previously been done. Put as much of the literature review as you can in the research proposal. Not just in the introduction, which should not be too long, but also later in the theory and the methods sections.

Research question

After discussing the general problem and the knowledge already available, refine the topic into a clearly formulated research question (and some sub-questions, if that helps clarifying the research objective)). Mention explicitly the type of question you want to answer (see section on research questions). Sometimes it is useful to refine the research question further after a short review of the theories you intend to use.

Theory/concepts

In this section, you should discuss the existing models, concepts and/or theories relevant to the topic, and say how these will inform your work. If the question is descriptive, the least you need is a clear conceptualization of the most relevant concepts. If the question is explanatory, just mentioning the relevant concepts is not enough, you will need the most relevant elements of the theory.

Research design

In this section you describe how you will go about answering your research question. Why is this approach suitable for answering the research question?

Case selection and sampling

How will you select your cases? If you select many cases what sampling technique is used? If you select only a few cases or one case, how did you select that case?

Data collection

In this section you should describe the data that will be used in your study, why these data are appropriate for testing the theories you have discussed, and how they will be collected. What type of data will you be using (e.g. quantitative or qualitative?). You may be collecting original data, or using an existing dataset.

Data analysis

On what basis will you draw causal inference, e.g. statistical inference using regression analysis, study of critical/extreme case.

Resources & timetable

You must think about how long the project will take and what resources it will involve. The project must of course be feasible in terms of time and money. Be realistic about this! Give a provisional schedule for the completion of the various parts of the project, (such as data collection) and the anticipated date of completion of the project as a whole.

Scientific and social relevance

Although you may have mentioned this in the introduction, it is good to pay attention to this topic in a broader sense. For example, in the introduction you may have stated that we still do not know why people vote in elections. In a part on the scientific and social relevance you may stress the importance of participation for the stability of democracy.

Provisional table of contents

Think about how you will structure the final report, and provide a provisional table of contents in line with this.

Not all bachelor- or master projects aim at generating generalized knowledge. Projects addressing applied questions like predictive questions, remedy questions and design questions, for example, apply the findings of existing research to address a particular problem (see section on research questions). In this case, it may not be possible or necessary to discuss research design, or case selection, for example. However, it will be necessary to have a more extensive literature review and a more extensive theoretical section, since you have to explicate which theory or theories you will apply. Since applying theories also involves measuring variables you will probably need sections about data collection and data analysis too.

How to formulate a research question?

Formulating a good research question is probably the most difficult part of your research project. Most of the time you start with a topic (energy policy, or human rights) or with a general problem (something is wrong with political participation, this production process, or human resource management). Sometimes the topic or problem you initially started with appears to be different from the one that is interesting. Be clear about the type of research question you want to answer. Several types of questions can be distinguished;

Normative questions are about what is allowed or what is good. These questions should not be confused with conceptual questions or descriptive questions (see below). In most cases normative questions implies philosophical (not empirical) research.

Conceptual questions are about the proper/useful/efficient meaning of words; ‘what is freedom?’, ‘what is equality?’ ‘Which types of markets can be distinguished’. Conceptualization is also a central part of research answering empirical questions, although conceptual questions in empirical research are often discussed and answered without explicitly stating a conceptual question.

Empirical questions are about ‘truth’ and ‘observations’. In science the goal of empirical questions is ‘inference’; generalization. There are several types of empirical questions, ranging from relatively simple to relatively complex.

- Descriptive questions (what is …). These questions are about describing facts, either at one point in time or over time. Once the concept you want to use is not directly observable (like ‘management style’ ‘political participation’) and/or the units of analysis are sets (like ‘consumers’, ‘firms’ or ‘politicians’) description also involves ‘inference’.

- Relational questions. These studies involve examining the relationship between different variables. They do not necessarily require that the relationship is causal.

- Explanatory questions (why is…). These questions are about explaining the causes for something. This requires that the relationship between different variables is studied. However, it is not enough to simply find correlations between variables; answering explanatory questions also requires that the cause precedes the consequence and that there is no third variable responsible for the correlation. In a ‘theory’ causes and consequences are connected by referring to a ‘causal mechanism’.

Applied questions are not aiming at finding or creating generalized knowledge, although they may involve some (mainly descriptive) inference. Applied questions are asked simply because people want to solve a specific social, political or commercial problem. Researchers aiming to answering applied questions, apply existing knowledge to solve a real world problem. Applied research is research using some part of the research communities' knowledge (theories, methods, and techniques) for a specific purpose. Applied research is often opposed to pure research (which is here called ‘empirical research’). Applied research questions can only be answered if empirical research questions have been answered first. We distinguish between different types of applied questions;

- Predictive questions (what will happen if …). Predictive questions are about things that will happen in the (still unknown) future. Using answers to relational questions (‘correlations’) or (preferably) explanatory questions (‘theories’) it is possible to make predictions that go beyond mythical thinking. If an existing correlation or proposition shows that ‘always when X, Y will occur too’, the observation that X is the case will help you to predict Y.

- Remedy questions (what is the solution to…). Remedy questions are about finding a solution to a specified problem based on previous research. Generally the solution proposed to such a question will be based around a causal relationship that has been established by existing research; ‘if you use remedy X, under circumstances C, Y will happen’. Your job is to summarize this research and show how it is relevant to the problem at hand. In addition you have to argue that the circumstances (C ) are relevant in your case. It will be necessary to include a much more detailed review of existing research than is done for other types of questions.

- Design questions (how to…). These questions are about coming up with an effective policy or an effective type of organization with a particular goal in mind. Design questions are similar to remedy questions, although the solution you propose may not necessarily be based on existing literature. Rather, you will be informed by the literature and come up with something new.

Since applied questions differ from empirical questions, students planning to answer a design question are referred to the webpage about applied science.

A special (sub-)category of questions are ‘unanswerable questions’. All types of questions can be ‘unanswerable’ too (given the existing level of (your) knowledge). Although it is difficult to say in general terms which questions are ‘unanswerable’, do not hesitate to admit that they are.

Readings

Basic readings

- Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 4.

- De Vaus, David (2001). Research Design in Social Research. London: Sage. Chapter 1.

Additional readings

- Gerring, John (2001) Social Science Methodology: a critical framework. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Part II.

How to conceptualize central variables?

Many of the concepts you might be interested in studying will have imprecise or vague meanings (e.g. ‘ productivity’, ‘happiness’ , ‘prejudice’). ‘Conceptualization’ refers to the process of specifying the meaning of concepts in a precise way. This involves specifying the ‘essential qualities’ associated with a concept, so that it becomes possible to tell whether or not something is an example of the concept. For example, the essential qualities of the concept ‘prejudice’ include ‘preconceived beliefs about specific groups of people’. Note that this conceptual definition does not refer to how the concept can be measured; it is abstract.

Many concepts contain a number of different aspects or dimensions. For example, ‘prejudice’ can relate to preconceived beliefs about different ethnic groups, different social groups, religious groups etc. It is important to specify the various aspects or dimensions of the concept. This forms the basis on which you operationalize and measure your variables.

Readings

Basic readings

- Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 5

- De Vaus, David (2001). Research Design in Social Research. London: Sage. Chapter 2.

- Shadish, William R., Thomas D. Cook and Donald T. Cambell (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Chapter 3.

Additional readings

- Gerring, John (2001) Social Science Methodology: a criterial framework. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, Ch. 3 and 4.

- Collier, Laporte and Seawright (2008) Typologies: Forming Concepts and Creating Categorical Variables, in: Box-Steffensmeier, Brady and Collier, Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, Oxford University Press.

- Gerring, John and Paul A. Baressi (2003) ‘Putting Ordinary Language to work. A min-max Strategy of Concept Formation in the Social Sciences’, Journal of Theoretical Politics, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 201-232

How to construct a useful theory?

Theories in social science are explanations; they propose a way to understand a particular aspect of the social world. If you seek to understand or explain empirical observations in your research, you will be required to engage with theory.

Example: Consider a study that examines the relationship between gender and academic achievement. If a strong relationship is observed, this in itself does not contribute to our understanding of the topic; the question still remains, why does the relationship exist? This is where theory comes in. A relevant theory in this instance will elaborate on the causal mechanism that links gender and academic achievement. This theory may rely on genetic arguments, or on arguments related to the social conditioning of girls and boys. Theories give mechanisms connecting variables.

A key characteristic of a good theory is that it is testable. That is, it must be possible to derive some specific hypotheses, which can be checked against the empirical evidence. These hypotheses are typically in the form of “if … then …”.

Examples of social science theories

Reinforcement theory: This theory seeks to explain the way in which people gather information. It is based on the assumption that people feel uncomfortable when their beliefs are challenged. It states that people seek out and remember information that provides support for their pre-existing attitudes and beliefs. A testable implication of this is that people are more likely to remember information that is in accordance with their prior beliefs than information that challenges their prior beliefs.

Differential association theory: this is a theory explaining how people become criminals. It posits that criminal behaviour is learned through social interaction with others. It predicts that the earlier in life an individual interacts with criminals, the more likely they are to become criminals themselves.

Neo-realist theory of international relations: this theory seeks to explain the behaviour of states in the international system. It is assumed that states are primarily motivated by the goal of survival and seek to maximize their power relative to other states. A testable implication of this is that if one state becomes powerful relative to others, then other states will seek to balance this power by increasing their capabilities or entering into strategic alliances.

Expectancy theory: this is a theory about the behaviour of employees. It assumes that employees’ behaviour is based on conscious choices among alternatives, with the goal of maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain. It predicts that if employees are offered clear rewards for productivity, then they will work harder.

Other related terms

Conceptual frameworks

As discussed on the page ‘conceptualization’, a conceptual framework is a set of clearly defined concepts that lead to the choice of variables to be used in a study. While a conceptual framework is essential, it in itself cannot provide an explanation for empirical findings.

Paradigms

A paradigm is an (often unstated) set of assumptions that shapes the way we interpret the world. In this sense, theories are more specific than paradigms, as theories propose explanations for specific phenomena. However, a broad set of theories can be said to be associated with a particular paradigm (e.g. the ‘rational choice paradigm’).

Models

A model is something less clearly defined. Models are abstract representations of something else. In the literature one can find models of conceptual frameworks (for example models making a distinction between various phases in a decision making process or making a distinction between various elements of an organization), models of a theory (for example abstract versions of the theory with boxes for the main variables and arrows for the causal connections) and even models of ‘facts’, like maps or miniature representations of buildings. Since the word model is not very clearly defined, students are advised not to use it or to clearly define what it means in the context of their project.

Readings

Basic readings

Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 2.

Additional readings

King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane and Sidney Verba (1994). Designing Social Inquiry: scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Chapter 3.

How to select a research strategy?

A research design refers to how you go about conducting your research. The choice of a research strategy is largely determined by the type of research question, the available means, and the units of analysis. Most introductory text books (including the one written by Earl Babbie, which is used at this faculty) do not distinguish clearly between research designs and data collection methods.

Research designs that can be used to explain things can be broadly categorised as either (quasi-)experimental, and as non-experimental. Within these two broad categories there are several sub-categories, depending on factors such as the number of groups analysed, the number of times each case is observed, and the number of cases.

(Quasi-)Experimental designs

Experimental designs refer to the broad category of research designs that involves at least two groups, administering a treatment and observing the consequences. Within this category, various sub-categories exist, depending on:

- How many groups are examined: A two-group design involves one control group and one treatment group. A factorial design involves several treatment groups, relating to different independent variables and different levels of these variables.

- How subjects are allocated to different groups: In true experiments, subjects are allocated to different groups on the basis of random assignment. In quasi-experiments, subjects are not allocated to different groups on the basis of random assignment.

- How many times the groups are observed: In post-test only designs, observations are only made after the treatment is administered. In pre-test post-test designs, observations are made both before and after the treatment is administered. When a series of observations are made before and/or after the treatment the design is even more complex.

Experiments (preferably using random assignment) are generally the best way to make valid causal inferences; however, many research questions are not amenable to experiments and the external validity of experiments is disputed.

Non-experimental designs

Non-experimental designs involve making observations with a single group. Within this category, various sub-categories exist, depending on:

- How many cases are studied: Quantitative non-experimental designs involve a large number of cases, often chosen by random selection, are also called ‘correlational designs’; qualitative designs involve a small number of cases or a single case.

- The number of time points at which observations are made: In cross-sectional designs observations are made at one point in time. In longitudinal designs repeated observations are made over time. Longitudinal designs can be further distinguished depending on whether the same units of observation are observed over time (panel studies), whether the same cohort is followed over time (cohort analysis) or whether only a series over random samples is used with different units of observation (trend studies).

Quantitative, non-experimental designs can be used to make accurate descriptive inferences about a population. This means they are strong at external validity. As ‘correlational designs’ they are also used to tackle explanatory questions. Qualitative research is the best approach to gaining insights into a topic with a view to developing hypotheses (exploratory research). Qualitative designs are also used to provide tentative tests of hypotheses on research questions that cannot be answered using experiments or quantitative non-experimental designs. The external validity of qualitative designs, however, is disputed. An extensive overview of qualitative designs can be found here.

Readings

Basic readings

- Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 4.

- Shadish, William R., Thomas D. Cook and Donald T. Cambell (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Chapters 1, 4-6.

- De Vaus, David (2001). Research Design in Social Research. London: Sage.

Additional readings

- Spector, Paul E. (1981). Research Designs. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Przeworski, Adam and Henry Teune (1970). The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. Malabar, Florida: Kreidger Publishing Company.

- King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane and Sidney Verba (1994). Designing Social Inquiry: scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lieberson, Stanley (1985). Making it Count: the improvement of social research and theory. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Yin, Robert K (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

How to select cases?

Social scientists try to make statements about a theoretical set of units. Sometimes we are able to study all units we are interested in. This means we study a census. In most cases, however, only a subset of cases is studied. Case selection is a crucial part of empirical research, and largely determines the extent to which you can generalise from your findings to the larger target population. Case selection is also called sampling, although this word is most frequently used when larger numbers of cases are selected. The main types of sampling are probability sampling and non-probability sampling. The first is mostly associated with large n studies. The second is associated with both large and smaller n studies. If the researcher does not have the intention to make an inference to a larger target population, other selection procedures are available.

Target population and sampling frame

The target population is the set of units we make statements about; companies, persons, newspaper articles, products. In many cases the target population is not easily accessed. A sampling frame is a set of units we can draw samples from. For example, if the target population is local businesses, a suitable sampling frame might be the listings in the business section of the telephone book. Preferably the sampling frame includes nearly all of the population, although this is not always possible. The sample frame is then used to select cases from.

Probability sampling

There are various types of probability sampling. All procedures use some reference to the known probability an element from the sampling frame is actually selected for study. Different procedures can be used to get a representative sample of units. A distinction is made between single stage sampling (for example, simple probability sampling, systematic sampling, stratified sampling and cluster sampling) and multi-stage sampling (in which different procedures are used sequentially (for example, first selecting municipalities and the random samples within each municipality).

Non-probability sampling

The set of non-probability sampling procedures is huge. Examples are self selection, snowball sampling and quota sampling. With all these procedures the danger is that the selection might be biased: i.e. over- or under- representing units with certain attributes. These procedures should therefore be avoided if possible.

If only a small number of cases is selected using probability sampling, the risk too is that certain attributes are over- or under-represented. To avoid this, cases must be selected on the basis of prior knowledge of their attributes (intentional selection). If the researcher tries to test a causal hypothesis het must at least select cases to ensure variation on the main independent and dependent variables. You cannot infer anything about the causes of the success of companies, for example, if you limit your selection to successful companies. Note, however, that if the number of cases is small, your conclusions can easily be the consequence of mere chance.

Selection of one case or only a few cases

If the researcher wants to explore a topic, or further develop an existing and well-tested theory several other case selection options are available. If the aim is exploration cases in single case studies are selected on the basis of the information they are expected to provide. Single cases can be selected because the case:

- is extreme (i.e. has an extremely low or high value on the central variable)

- is critical (i.e. ‘If it is valid for this case, it is valid for all (or many) cases’ or the converse, ‘If it is not valid for this case, then it is not valid for any (or only few) cases.’)

- is typical (i.e. an example of the phenomenon under investigation)

- is deviant (i.e. has a combination of characteristics different from most other units)

Note that all case selection procedures mentioned here assume the existence of a (preferably tested) theory and some general knowledge of the central variables in the units of analysis on the basis of which single cases can be selected.

Readings

Basic readings

- Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 7.

- Shadish, William R., Thomas D. Cook and Donald T. Cambell (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Chapter 3.

- De Vaus, David (2001). Research Design in Social Research. London: Sage. Chapters 5, 8, 11, 14.

Additional readings

- King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane and Sidney Verba (1994). Designing Social Inquiry: scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Yin, Robert K (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Swanborn, P. G (1996). Case-study’s: Wat, wanneer en hoe? Amsterdam: Boom.

- Franzosi, Roberto P. (2004). Content Analysis, in: Melissa A. Hardy and Alan Bryman (eds). Handbook of Data Analysis. London, Sage

- Berg, Bruce (2007) Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Boston, Pearson.

- Gerring, John (2001) Social Science Methodology: a criterial framework. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chapter 8.

How to operationalize and measure variables?

Having already specified the concepts you are interested and produced a list of dimensions for each concept, the next stage is to operationalize and measure your variables. The dimensions of a concept form the basis for a list of indicators of the concept: for instance, the indicators of prejudice might include ‘negative attitudes or behaviour towards women’; ‘negative attitudes or behaviour towards ethnic minorities’ etc. Note that while the concept itself and the dimensions of the concept are abstract, the indicators refer to behaviour that can be observed.

You must also decide what level of measurement to use for each indicator. It is important that the variable is exhaustive, meaning that every observation can be placed into one of its categories.

As you may end up with several variables related to different dimensions of a single concept, it may be necessary to combine these variables in some way so as to arrive at one overall measure. An ‘index’ is a measure which combines several different pieces of information. For example, an IQ score is an index based on a person’s response to a large number of questions. Similarly, an index of ‘prejudice’ can be made based on a person’s responses to several questions related to this concept. An index is usually an ordinal measure. It is also possible to arrive at a composite measure that is nominal; this is known as a ‘typology’. For instance, you may combine several indicators of political ideology to develop a four-fold typology of political parties.

Given the complexities involved, it is necessary to assess how good the final measurements are. The two most important criteria are reliability and validity. Validity refers to bias in the measurement: is it really measuring what it is supposed to measure? Reliability refers to the certainty that the same measurement would be made if the research was repeated. Further information on measurement reliability can be found here and here.

Readings

Basic readings

- Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapters 5 & 6.

- De Vaus, David (2001). Research Design in Social Research. London: Sage. Chapter 2.

- Shadish, William R., Thomas D. Cook and Donald T. Cambell (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Chapters 2 and 3.

Additional readings

- Collier, Laporte and Seawright (2008) Typologies: Forming Concepts and Creating Categorical Variables, in: Box-Steffensmeier, Brady and Collier, Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, Oxford University Press.

How to collect data?

Many research projects require the collection of new data. However, this is not always necessary - you should investigate what datasets are already available. Some information and useful links to research data repositories can be found on this website of the OpenAIRE AMKE non-profit organization.

Data collection methods can be divided into two broad categories, obtrusive and unobtrusive data collection. This refers to whether the researcher influences the units of observation while collecting data or not. Both obtrusive and unobtrusive data collection methods can be used to collect various different types of data. An important distinction in terms of types of data is between quantitative qualitative data. When data is recorded in numerical form and entered into a data matrix, it is known as quantitative data. When it is not recorded in numerical form, it is known as qualitative data.

Obtrusive data collection methods

If the target population is a set of individuals, data are typically collected using surveys or interviews. Interviews and surveys are ‘obtrusive’ data collection methods, because the individuals being studied are aware that they are being studied, and this may affect their behaviour (answers).

There are various types of surveys such as internet surveys, telephone surveys and postal surveys. Programmes such as Google Docs can help you to make an online survey, although other services are available too, like SurveyMonkey. Students and employees of the University of Twente can get access to Qualtrics. This allows you to collect data via the web. Responses from a survey can then be entered into a data matrix for analysis.

If only a small number of individuals are asked about a lot of topics, you normally use interviews. In ‘structured interviews’, each interviewee is asked the same questions in the same order, and usually there is a set of multiple choice answers specified in advance. Data from structured interviews can be treated much like a survey, and the results entered into a data matrix. ‘Unstructured interviews’ are used to gain an understanding of a topic or phenomenon: here, the questions often change from one interview to the next, and the interviewee is not given fixed set of answers to choose from. Information gained in unstructured interviews is not used to produce a data matrix for statistical analysis.

Unobtrusive data collection methods

It is also possible to gather information in such a way that that the individuals (or companies, groups etc) that you are studying are not aware that you are doing so, and your research will not affect their behaviour. Many forms of information exist that are recorded for purposes other than scientific research, yet can be later used for this purpose. Examples include data on crime, hospital admissions, house prices, employment, or road accidents. Many of these types of data can be found on national statistics websites such as Statistics Netherlands. There are also many sources of information in the form of recorded communication that can be used as a source of data, such as newspaper coverage of particular topics over time or across countries; election manifestos of political parties etc. Content analysis is used to collect data from documentary sources. Content analysis is often used in a way that produces quantitative information that can be placed in a data matrix. As a student of UT, you can use ATLAS.ti for this, which you can download from our Notebook Service Centre.

Readings

Basic readings

- Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapters 8-11.

- De Veaux, Richard, Paul Velleman and David Bock (2008). Stats: Data and Models (2nd edition). London: Pearson/Addison Wesley. Part III.

Additional readings

- Becker, Howard S (1998). Tricks of the Trade: how to think about your research while you’re doing it. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hammersley, Martyn (1992). What’s wrong with Ethnography? London: Routledge.

- Yin, Robert K (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Webb, Eugene J., Donald T. Cambell, Richard D. Schwartz and Lee Sechrest (2000). Unobtrusive Measures (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, California.

- Groves, Robert M., Floyd J. Fowler and Mick P. Couper (2004) Survey methodology. Hoboken, Wiley-Interscience.

How to select the appropriate statistical test and how to analyze data?

There are a large number of techniques for analyzing data. Which techniques you have to use depends on what you want to do and also on the type of data you are using. Descriptive statistics are used to show the central tendency (e.g. mean) and dispersion (e.g. standard deviation) of a single variable, or the strength and direction of the relationship between two or more variables. Inferential statistics are concerned with making generalised conclusions on the basis of your data – in other words, when you are trying to infer whether patterns observed in the data also exist in some wider population. Inferential statistics involve conducting statistical ‘tests of significance’. For both types of analysis, the choice of technique is shaped by the type of variables you are using – that is, the level of measurement of your variables.

Textbooks and online resources should be consulted to help you decide on the appropriate techniques to use. To start with, you can also use this online tool for selecting statistics. This tool asks you a series of questions and then tells you which techniques are appropriate for your analysis. Before using this tool, you should decide:

- how many variables you want to analyze together

- the level of measurement of these variables

- whether you are interested in describing a single variable, measuring the strength of a relationship or performing a test of significance

More detailed information about statistical techniques can be found in the textbooks listed below, or on websites such as statsoft.com

To analyze data, you will need a statistical software package such as SPSS (you can find out how to get it here). The ‘Handbook of Statistical Analysis Using SPSS’ provides a very clear and complete text on statistics and the use of SPSS. Other useful statistical software packages include STATA and Minitab.

You may need to refresh your knowledge on algebra in order to understand some of the concepts and techniques involved in statistical analysis. The SOS website provides a good introduction.

In order select the correct method of analysis for (1) comparing groups or (2) identifying relationships, you can have a look here.

Readings

Basic readings

- Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 16.

- De Vaus, David (2001). Research Design in Social Research. London: Sage. Chapters 6, 9, 12.

- De Veaux, Richard, Paul Velleman and David Bock (2008). Stats: Data and Models (2nd edition). London: Pearson/Addison Wesley.

Additional readings

- Agresti, Alan and Barbara Finlay (1997) Statistical Methods for the Social Sciences. Upper Saddle River, Pearson.

- Agresti, Alan (2007) An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis. New York, Wiley

- Woolridge, Jeffrey M. (2009) Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach (4th edn). Mason: South-Western.

- Carroll, J. Douglas and Paul E. Green (1997). Mathematical Tools for Applied Multivariate Analysis (2nd edition). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Achen, Christopher (1982) Interpreting and using regression. London, Sage

- Andersen, Robert (2008) Modern Methods for robust regression. London, Sage

- Fox, John (2008) Applied Regression Analysis and Generalized Linear Models. London, Sage

- Gelman, Andrew and Jennifer Hill (2007) Data Analysis using Regression and Multilevel/ Hierarchical Models. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

- Hardy, Melissa A. and Alan Bryman (eds) (2004). Handbook of Data Analysis. London, Sage.

How to report about my research project?

While each research project is different, the basic structure should be essentially the same for every write-up. Reports should generally include the following sections (although the headings on these sections can bear different names, and some research questions might require a different format):

The following is a list of some of the things you might want to check before submitting your thesis to ensure a good result.

Introduction

I clearly define my research question (question, not topic!) and spell out what it is that I want to study

I discuss how my thesis relates to existing research

I summarize my main arguments and findings

Theory

I discuss how the existing literature applies to my research question (literature review, not summary!)

I discuss the assumptions and concepts used in the theory

I formulate one or several hypotheses which specify the theoretically expected causal relationship between my dependent and independent variables

Research Design and Measurement

I provide sufficient information for a reader to critically evaluate or replicate my study

I discuss my choice of research design

I discuss my case selection

I discuss how the theoretical concepts are measured

I discuss possible limits of my measurement

I use diagrams and tables where appropriate

Data and Analysis

I describe the data to give my reader a good overview of the empirical content of my study

I provide sufficient information for a reader to critically evaluate or replicate my study

I explain how I interpret my findings

I state whether or not my hypotheses have been corroborated

I discuss the limits of my findings (e.g., threats to validity)

I use tables and graphs where appropriate

Conclusion

I give an answer to the research question posed at the beginning.

I summarize what I did and how I did it.

I relate my findings to the wider literature in my subfield and (where appropriate) discuss policy implications

I discuss the limits of my study and (possibly) future research directions

Use examples of published articles in academic journals as a guide to writing and presenting your report. Follow the APA style guide when writing your report and referencing your paper. More information on reporting standards can be found here. A study help in Dutch for writing clear theses can be found here.

Basic readings

Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 17.

How to apply generated knowledge to address actual problems?

Applied questions are asked to solve a specific social, political, organizational or commercial problem. Applied questions do not aim at generating general knowledge. Some elements belonging to ‘scientific research designs’ are therefore not relevant for and not included in ‘applied science project descriptions’. Of course, applied questions can only be answered systematically if some empirical research questions have been answered first. Otherwise there is nothing to apply.

The systematic discussion of research designs and data collection methods in introductory text books occur in the context of ‘generating general knowledge’ and ‘inference’. The area of applied science is less standardized. On this website we distinguish between several types of applied research: descriptions, evaluations and predictions, remedy selections and designs.

Descriptions and interpretations

Example: What are the needs of our clients? How do people feel about our company? What happened during the decision making process that led to the adoption of the law banning smoking from public places?

Descriptive questions in the context of applied research are similar to descriptive questions in empirical research and oftentimes involve ‘inference’ too, because we often want to say rather abstract things (‘quality’) about abstract units (‘the school’). The aim of this type of research is to describe characteristics of a limited (finite) set of units (clients, people, companies). In this type of research you start with a conceptualization of the variables you intend to use. In the literature you can find models, typologies, or classifications (sometimesd confusingly called ‘theories’) to describe your units. In the data analysis section, you may want to break up the results to different sub-sets (man/women; different units within the company). Note, however, that questions of inference are still relevant. Does the way you measure your central variable(s) allow you to make a general statement; and does the study of a subset of the units allow you to say something about all units? Theory can be relevant too. If you want to describe and understand why something happened in a particular case, you need a theory to decide what aspects of reality to look at.

Predictions, ex post and ex ante evaluations

Example: Did the policy work as intended? Will the decision work out as intended? What are our market prospects?

Evaluations can be asked before (ex ante) or after (ex post) a decision is made. If the evaluation is asked before the actual decision, the only research strategy available is to use existing (correlational or causal) knowledge about the known effects of some course of action to explain why the decision may or may not work as intended.

Example: Suppose that a manager wants to know whether the strategy to target a specific set of customers will work out, given some known market conditions. This means the manager has to turn to some theory helping her to understand the possible consequences of this type of action.

If the evaluation is asked after the actual decision is made and after possible effects may have occurred, a researcher can also use an interrupted time series design to study the possible effects of the decision. In that case the design is similar to ‘standard’ explanatory research designs.

More information on evaluation research can be found here.

Remedies

Example: Which of a set of strategies is best under the current circumstances?

If a set of potential remedies is available, you have to select these remedies on the basis of a set of criteria including availability, costs, and effectiveness. The basis of this comparison is a list of all potential remedies, a set of criteria and a ‘score card’. If you put the potential remedies in the rows and the criteria in the columns of a matrix, the scores can be put in the cells. To establish the effectiveness of the various remedies, one needs (the results of) empirical research, showing that a specific remedy is better with some criterion than some other remedy. Techniques are developed in cost-benefit analysis and multi-criteria analysis to assess the score cards.

Design

Example: What should we do about this problem?

Everyone can build a house, but will it meet the formal requirements, will it stand a storm, and will it be affordable? Everyone can design a policy to reduce the amount of litter on streets, but are you allowed to implement that policy, how much will it cost and will it help? Some people will argue that this is not a scientific question, but scientifically established knowledge can be useful to design something new.

If you plan to design systematically, you first have to establish the goals and to define a set of criteria and demands which have to be met. Secondly, existing designs (when available) have to be evaluated against this set of demands. Thirdly, a new design is made using as much information as you can. This design is made individually (by just being creative) or in a group (as in a ‘brain storm session’). Fourthly, the news design is evaluated using the pre-established set of criteria, (compared with existing designs if available) and tested. Of course, this is an on-going process and may include a repetition of step 3 and 4 several times. The ‘testing phase’ is similar to the aforementioned evaluation studies and may even include a proper experiment. In the literature the steps in a design process are presented in various ways, but include all four steps mentioned here.

Basic readings

Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 12.

How to be ethical?

There are a number of ethical considerations to be aware of before conducting your research. For instance, individuals participating in surveys and experiments must do so voluntarily and in full awareness of what they are getting into, with suitable guarantees of confidentiality or even anonymity. While ethical issues are generally less salient when conducting qualitative research using unobtrusive measures (like a document analysis), it is always important to be aware of these issues.

It is also important to maintain high ethical standards when reporting your research. Key issues here include accurate reporting, avoiding plagiarism, and proper acknowledgment of the work you draw on. Guidelines on this can be found here.

For the BMS faculty, there is a website of the BMS ethics committee. The committee facilitates and monitors the ethical conduct of all research on humanities and social sciences involving human beings in UT faculties. You can also submit your research project for ethical approval there. The website can be found here.

Basic readings

- Babbie, Earl (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th edition). Cengage. Chapter 3.

- Shadish, William R., Thomas D. Cook and Donald T. Cambell (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Chapter 9.

- De Vaus, David (2001). Research Design in Social Research. London: Sage. Chapters 5, 8, 11, 14.

How to plan my project?

Dissertations are large and complex projects, so organisation and time management are crucial. Having a detailed research plan will help you to keep on schedule.

To create a research plan, work out how long you have to complete the project. Divide this period into weeks. For each week write down what you will be doing. To start, you will need to think about the main tasks that you are facing and how long they will take. These include:

- Literature review: This will involve an intense period of reading; it is important to get this done as quickly as possible. Careful note-taking will save a lot of time later.

- Empirical research/data collection: This is perhaps the most difficult task to predict in terms of timing, as it may be dependent on factors outside of your control. For instance, you may be conducting interviews, and so depend on the availability of others. Make sure you allow plenty of time for unforeseen delays.

- Data analysis

- Writing first draft

- Revisions/second draft (in response to comments from your supervisors)

- Editing and correcting

You may want to use an organisational tool such as a Gantt chart which allows you to compare your progress against your goals for each task.

Be realistic about your research plan. For instance, it is important to allow time in the plan for other things that you will be doing (such as holidays, for example), and to leave enough time for revisions. Remember that you will encounter some problems along the way, so build in some leeway in the plan for this.

Once you have completed a draft research plan, discuss it with your supervisor. Together, work out a schedule of meetings where you can review your progress.

Useful links on planning a dissertation can be found here and here.

The research methods toolbox is developed by the Henk van der Kolk, Rory Costello …***

The toolbox makes substantial use of:

Trochim, William M. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2nd Edition. URL: https://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/

How to construct a questionnaire

QUESTIONNAIRE CONSTRUCTION

In this section, you can find information that can help you to construct your questionnaire. We have a number of videos that help you with constructing your survey and that help you construct your scale. Additionally, you can find information on how to prepare your data after data collection and further information on psychometric tests and questionnaire tools like atlas.ti.

Construction of a survey and scale

Videos about the construction of a survey:

Videos about what to pay attention to when constructing a scale

Preparing data for further ANALYSIS

Videos about the data of a questionnaire

Coding of the variables and the data matrix

Coding of multiple variables and open-ended questions

What do you do with missing data en how do you check data?

Psychometric Tests

An introduction in psychometric tests.

Do you want to calculate the cut-off in a psychometric test? You can use the receiver operating characteristic analysis gebruiken and you can read more about that here.

Atlas.TI

Do you use ATLAS.ti for your qualitative research? See here how you should do that.

APA Guides

APA

Here you can find a selection of websites that can help you to write your research in line with APA guidelines:

- For the layout of your article (headings, font, tables & figures), see this website of the American Psychological Associaton (APA).

- For how to format your reference list, see example references on the APA website.

- For in-text citations, see examples here on the APA website.

- For an example report, visit this APA website.

- For numbers and statistics, see the APA's guide on reporting numbers and statistics.

- For more information have a look at the official website of APA!

2. Analysing your data

Preparing your data

Preparing your data

After you collected your data you often obtain a file with all your variables. To prepare your data for data analysis you often have to clean your data. This includes:

- Cleaning your data (e.g. deleting variables that you do not need)

- Handle missing data

- Prepare your data set (long format vs. wide format)

Information on how to do this in R and an explanation can be found here.

Descriptive statistics

For descriptive statistics think about the mean, standard deviations, correlation tables, and sampling characteristics. Make sure to think about what suits best to your data and how you want to display it. Check under 1. Getting started --> APA Guides for how you can best write it up in APA.

You can use chapters 1-3 of the book or the R-helpdesk website to see how to run descriptive statistics in R.

Find an overview of the difference between descriptive and inferential statistics on the following website Understanding Descriptive and Inferential Statistics | Laerd Statistics.

Assumptions and nonparametric tests

For linear models the following assumptions should be met (see Chapter 7):

- Linearity

- Equal variance/ Homoscedasticity

- Normal distribution of residuals

- Independence (except for linear mixed models)

If the assumptions are not met, you have two options:

Linear model and statistical tests

STATISTICAL TESTS

The traditional approach is based on a number of statistical tests where every single test has its own formula and tests a very specific null-hypothesis. The approach of linear modelling works with first specifiying a linear model for the data. For the inference regarding statistical significance it is not important which approach is used. However, there are two main advantages of the linear model. First, the family of linear models is so large that you can test infinitely more hypotheses with a linear model than with a specially-designed test-statistic. Second, the syntaxes of SPSS and codes used in R all follow the same structure which makes it more accessible and understandable.

Linear model

At the University of Twente we encourage students to use linear models for their statistical analyses. Also we as the Methodology Shop would like to advise you to focus on linear models.

Generally, linear models follow the structure of y=b0 + b1x1 + b2x2 + ... + e. This is often recognized as a regression model which is one form of a linear model. By including categorical variables you can extend the model and cover ANOVA-type of analyses. The linear models themselves can also be extended to linear mixed models to model dependencies in the data, e.g. when you used repeated measures, clustered data, multilevel etc. Also, generalized linear models can be used to model non-numeric dependent variables, such as dichotomous (e.g. logistic regression) or when your data consist of counts (poisson regression).

BELOW YOU CAN FIND AN OVERVIEW OF WHAT IS THE BEST LINEAR APPROACH TO ANSWER YOUR RESEARCH QUESTION

To be able to choose the right approach you need to know what you dependent and independent variables are. You also need to know what type of variables you have (e.g. categorical, numerical etc.). Please write this down first and have a look at this overview afterwards.

The mentioned chapters refer to the following book.

Models with a Numeric Dependent Variable without a Clustering Variable

| Old approach | New approach | Relevant chapters |

|---|---|---|---|

Comparing two means from two independent samples | Independent samples t-test | Linear model with

| Chapter 6 |

Comparing more than two means from independent samples | One-way analysis of variance | Linear model with

| Chapter 6 |

Testing the interaction effect of two categorical variables on a numeric dependent variable | Factorial analysis of variance | Linear model with

| Chapter 9 |

Testing the interaction effect of two numeric variables on a numeric dependent variable | Regression analysis | Linear model with

| Chapter 9 |

Testing the interaction effect of one independent numeric variable and one numeric dependent variable | - Not possible | Linear model with

| Chapter 9 |

Regression | Linear regression analysis | Linear model with

| Chapter 4 and Chapter 6.5 |

Models with a Numeric Dependent Variable and a Clustering Variable (due to Repeated Measures or ESM)

Old approach | New approach | Relevant chapters | |

|---|---|---|---|

Comparing two means from two related samples | Paired samples t-test | Linear mixed model with

| Chapter 12 |

Comparing more than two means from related samples | Repeated measures ANOVA | Linear mixed model with

| Chapter 13 |

Analysing data from ESM studies | Linear mixed model with

| Chapter 12 & Chapter 13 |

Additional information for analysing data from ESM studies:

To analyse your data, make sure to have your data in a long-format (one observation per row).

Here you find information how to do the analysis in SPSS.

Person Mean (PM) and Person-mean centering (PMC)

In case you want to distinguish between- and within-person effects it is important to apply person-mean centering. This article explains in detail how to do this and what the rationale behind it is.

Models with a Dummy or a Count Dependent Variable

Old approach | New approach | Relevant chapters | |

|---|---|---|---|

Logistic regression | Logistic regression analysis | Generalized linear model with

| Chapter 15 |

Testing the independence of two categorical variables | Pearson chi-square test | Generalized linear model with

| Chapter 16 |

3. Statistical softwares

Depending on when you started your studies you learned statistics either with the software SPSS (starting your Bachelor before 2020) or with R (starting your Bachelor in 2020 and later). Find below the most important commands for either software:

R

Basic code structure for Linear models

Linear models with numeric dependent variable and no clustering variable

| Linear model used | Relevant chapters | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

Comparing two means from two independent samples | Linear model with

| Chapter 6 |

|

Comparing more than two means from independent samples | Linear model with

| Chapter 6 | If x is a factor variable

If x is stored as a numeric variable

|

Testing the interaction effect of two categorical variables on a numeric dependent variable | Linear model with

| Chapter 9 | If x and z are factor variables

|

Testing the interaction effect of two numeric variables on a numeric dependent variable | Linear model with

| Chapter 9 | If x and z are numeric variables

|

Testing the interaction effect of one independent numeric variable and one numeric dependent variable | Linear model with

| Chapter 9 |

|

Regression | Linear model with

| Chapter 4 and 6.5 |

|

MODELS WITH A NUMERIC DEPENDENT VARIABLE AND A CLUSTERING VARIABLE (DUE TO REPEATED MEASUREMENTS)

New approach | Relevant chapters | Code | |

|---|---|---|---|

Comparing two means from two related samples | Linear mixed model with

| Chapter 12 |

|

Comparing more than two means from related samples | Linear mixed model with

| Chapter 13 |

|

MODEL WITH A DUMMY OR A COUNT DEPENDENT VARIABLE

New approach | Relevant chapters | Code | |

|---|---|---|---|

Logistic regression | Generalized linear model with

| Chapter 15 |

|

Testing the independence of two categorical variables | Generalized linear model with

| Chapter 16 |

|

Manuals & Websites

Please keep in mind that when working with R it is normal to search for the specific codes needed.

The UT provides a manual with different R codes for several types of analyses. It is mainly aimed at codes used in the statistics courses of several Bachelor programmes but can be a good starting point.

If you need information on how to analyse data using linear models you can have a look at this book.

If you have questions regarding Bayesian statistics please have a look at this book. It also provides information on how to set up R and how to install libraries from cran but also other sources.

SPSS

BASIC SYntax STRUCTURE FOR LINEAR MODELS

Linear models with numeric dependent variable and no clustering variable

| Linear model used | Relevant chapters | Syntax |

|---|---|---|---|

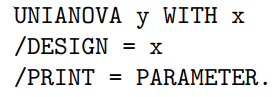

Comparing two means from two independent samples | Linear model with

| Chapter 6 | If x is a dummy variable

If x is not dummy-coded

|

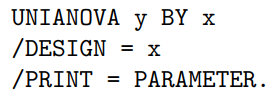

Comparing more than two means from independent samples | Linear model with

| Chapter 6 |

|

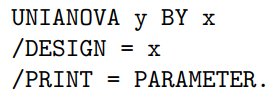

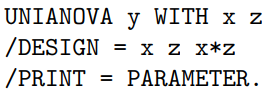

Testing the interaction effect of two categorical variables on a numeric dependent variable | Linear model with

| Chapter 9 |

|

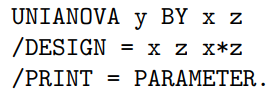

Testing the interaction effect of two numeric variables on a numeric dependent variable | Linear model with

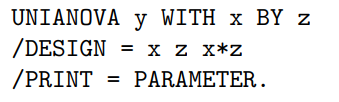

| Chapter 9 |

|

Testing the interaction effect of one independent numeric variable and one numeric dependent variable | Linear model with

| Chapter 9 |

|

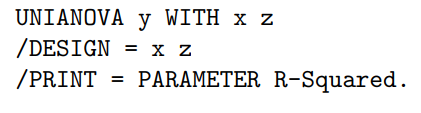

Regression | Linear model with

| Chapter 4 and 6.5 |

|

Models with a numeric dependent variable and a clustering variable (due to repeated measurements)

New approach | Relevant chapters | Code | |

|---|---|---|---|

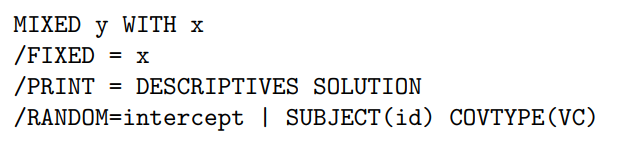

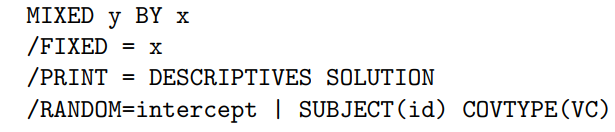

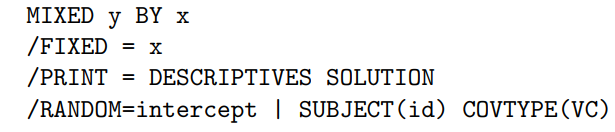

Comparing two means from two related samples | Linear mixed model with

| Chapter 12 | If x is a dummy variable

If x is not dummy-coded

|

Comparing more than two means from related samples | Linear mixed model with

| Chapter 13 |

|

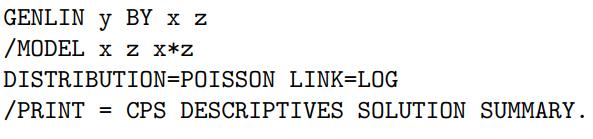

Model with a dummy or a count dependent variable

New approach | Relevant chapters | Code | |

|---|---|---|---|

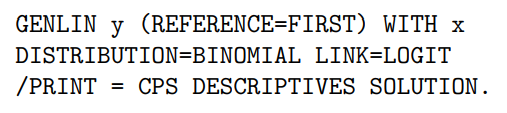

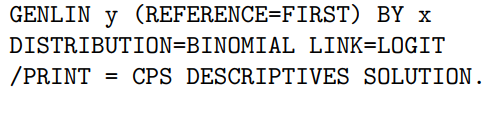

Logistic regression | Generalized linear model with

| Chapter 15 | If x is numeric or dummy-coded

If x is a non-dummy categorical variable

|

Testing the independence of two categorical variables | Generalized linear model with

| Chapter 16 |

|

The general commands useful to analyse data using linear models are

Linear model | UNIANOVA |

Linear mixed model | MIXED |

Generalized linear model | GENLIN |

Further information

Here you can find some useful websites that explain how to carry out certain analyses in SPSS.

SPSS tutorials | The Ultimate Guide to SPSS (spss-tutorials.com)

The website below is very useful but the full package costs. Therefore, there is no overview page of all available statistical tests and how to perform these in SPSS. Below you find an example page for a regression analysis. For all other statistical tests, please use google to see whether statistics.leard has a manual available for free.

Finally, this website provides a theoretical overview of different tests and how to conduct these in SPSS. Just type the test you would like to use into the search bar.

4. Schedule a consult

When to make an appointment

If you still need additional support after you followed our step-by-step guide, the methodology shop offers help via email and in the form of an online consult. A consult is often preferred over an email, as only small/general questions can be answered via email. Please schedule a consult at least 24 hours in advance (weekdays!).

A consult is by default online through MS Teams, you will receive a meeting invitation prior to the meeting.

Use this tool to schedule a consult: METHODOLOGYSHOP Planner (utwente.nl)

FYI: The consultants can give advice on how and when to run a certain analysis, but will not carry out any analyses for you.

For all kinds of other questions, including small/general questions about research methodology or statistics, please send an email (in English) to methodologyshop@utwente.nl We will try to answer your email as soon as possible, but please note that it might take several days before you receive an answer.

Consultants:

Barbara Chrzescijanska (General, R, SPSS)